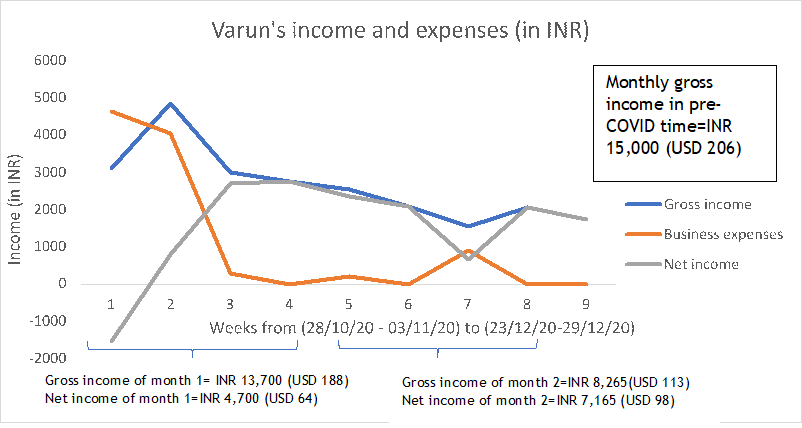

Corner shop owner Yuyun finds it difficult to connect to the internet on her phone from her village of Gunungpayung in the hilly terrain of Temanggung regency. The village in Central Java lies 458 kilometers east of the capital of Jakarta. Yuyun sells daily necessities from a corner shop in her home. She also runs a coffee roasting business in the village. She is one of our diarists from MSC and L-IFT’s

Corner Shop Diaries project. Gunungpayung is not the only rural area in Indonesia that has no or limited internet access.

Reports indicate that access to 4G networks evades

12,548 villages in the country. While 90% of 4G signals are available in urban areas, the number falls to

only 76% in rural areas. In Java, the most developed and populous island in the archipelago, the internet penetration rate is

only 56.4%. In less populous islands, such as Sulawesi and Papua, the rate of internet penetration falls to

below 10%. This inequality results from

various factors, including geographical conditions, a notion among providers that rural and sparsely populated areas are not profitable, and a lack of regulation in infrastructure and frequency-sharing.

Recent Comments